Decades ago, a young naval engineer on a British nuclear submarine started taking an interest in the electric batteries helping to run his vessel. Silently running under the frozen polar ice cap during the Cold War, little did this submariner know that, in the 21st century, batteries would become one of the biggest single sectors in technology. Even the planet. But his curiosity stayed with him, and almost 20 years ago he decided to pursue that dream, born many years beneath the waves.

The journey for Trevor Jackson started, as many things do in tech, with research. He’d become fascinated by the experiments done not with lithium batteries, which had come to dominate the battery industry, but with so-called “aluminum-air” batteries.

Technically described as “(Al)/air” batteries, these are the — almost — untold story from the battery world. For starters, an aluminum-air battery system can generate enough energy and power for driving ranges and acceleration similar to gasoline-powered cars.

Sometimes known as “Metal-Air” batteries, these have been successfully used in “off-grid” applications for many years, just as batteries powering army radios. The most attractive metal in this type of battery is aluminum because it is the most common metal on Earth and has one of the highest energy densities.

Think of an air-breathing battery which uses aluminum as a “fuel.” That means it can provide vehicle power with energy originating from clean sources (hydro, geothermal, nuclear etc.). These are the power sources for most aluminum smelters all over the world. The only waste product is aluminum hydroxide and this can be returned to the smelter as the feedstock for — guess what? — making more aluminum! This cycle is therefore highly sustainable and separate from the oil industry. You could even recycle aluminum cans and use them to make batteries.

Imagine that — a power source separate from the highly polluting oil industry.

But hardly anyone was using them in mainstream applications. Why?

Aluminum-air batteries had been around for a while. But the problem with a battery which generated electricity by “eating” aluminum was that it was simply not efficient. The electrolyte used just didn’t work well.

This was important. An electrolyte is a chemical medium inside a battery that allows the flow of electrical charge between the cathode and anode. When a device is connected to a battery — a light bulb or an electric circuit — chemical reactions occur on the electrodes that create a flow of electrical energy to the device.

When an aluminum-air battery starts to run, a chemical reaction produces a “gel” by-product which can gradually block the airways into the cell. It seemed like an intractable problem for researchers to deal with.

But after a lot of experimentation, in 2001, Jackson developed what he believed to be a revolutionary kind of electrolyte for aluminum-air batteries which had the potential to remove the barriers to commercialization. His specially developed electrolyte did not produce the hated gel that would destroy the efficiency of an aluminum-air battery. It seemed like a game-changer.

The breakthrough — if proven — had huge potential. The energy density of his battery was about eight times that of a lithium-ion battery. He was incredibly excited. Then he tried to tell politicians…

Despite a detailed demonstration of a working battery to Lord “Jim” Knight in 2001, followed by email correspondence and a promise to “pass it onto Tony (Blair),” there was no interest from the U.K. government.

And Jackson faced bureaucratic hurdles. The U.K. government’s official innovation body, Innovate UK, emphasized lithium battery technology, not aluminum-air batteries.

He was struggling to convince public and private investors to back him, such was the hold the “lithium battery lobby” had over the sector.

This emphasis on lithium batteries over anything else meant U.K. the government was effectively leaving on the table a technology which could revolutionize electrical storage and mobility and even contribute to the fight against carbon emission and move the U.K. toward its pollution-reduction goals.

Disappointed in the U.K., Jackson upped sticks and found better backing in France, where he moved his R&D in 2005.

Finally, in 2007, the potential of Jackson’s invention was confirmed independently in France at the Polytech Nantes institution. Its advantages over Lithium Ion batteries were (and still are) increased cell voltage. They used ordinary aluminum, would create very little pollution and had a steady, long-duration power output.

As a result, in 2007 the French Government formally endorsed the technology as “strategic and in the national interest of France.”

At this point, the U.K.’s Foreign Office suddenly woke up and took notice.

It promised Jackson that the UKTI would deliver “300%” effort in launching the technology in the U.K. if it was “repatriated” back to the U.K.

However, in 2009, the U.K.’s Technology Strategy Board refused to back the technology, citing that the Automotive Council Technology Road Map “excluded this type of battery.” Even though the Carbon Trust agreed that it did indeed constitute a “credible CO2-reduction technology,” it refused to assist Jackson further.

Meanwhile, other governments were more enthusiastic about exploring metal-air batteries.

The Israeli government, for instance, directly invested in Phinergy, a startup working on very similar aluminum-air technology. Here’s an, admittedly corporate, video which actually shows the advantages of metal-air batteries in electric cars:

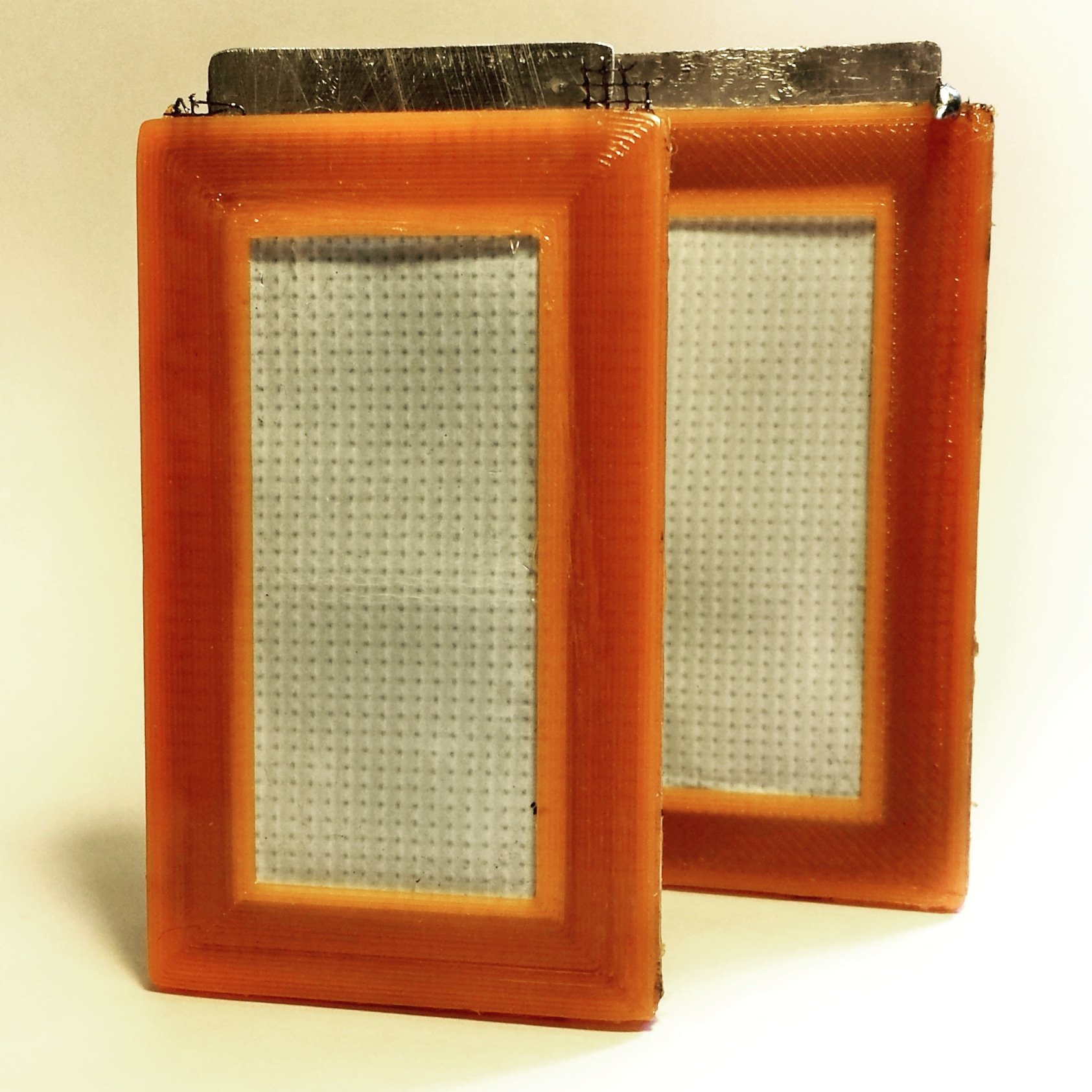

He worked closely with Lotus Engineering to design and develop long-range replacement power packs for the Nissan Leaf and the Mahindra Reva “G-Wiz’ electric cars. At the time, Nissan expressed a strong interest in this “Beyond Lithium Technology” (their words) but they were already committed to fitting LiON batteries to the Leaf. Undeterred, Jackson concentrated on the G-Wiz and went on to produce full-size battery cells for testing and showed that aluminum-air technology was superior to any other existing technology.

And now this emphasis on lithium-ion is still holding back the industry.

The fact is that lithium batteries now face considerable challenges. The technology development has peaked; unlike aluminum, lithium is not recyclable and lithium battery supplies are not assured.

The advantages of aluminum-air technology are numerous. Without having to charge the battery, a car could simply swap out the battery in seconds, completely removing “charge time.” Most current charging points are rated at 50 kW which is roughly one-hundredth of that required to charge a lithium battery in five minutes. Meanwhile, hydrogen fuel cells would require a huge and expensive hydrogen distribution infrastructure and a new hydrogen generation system.

But Jackson has kept on pushing, convinced his technology can address both the power needs of the future, and the climate crisis.

Last May, he started getting much-needed recognition.

The U.K.’s Advanced Propulsion Centre included the Metalectrique battery as part of its grant investment into 15 U.K. startups to take their technology to the next level as part of its Technology Developer Accelerator Programme (TDAP). The TDAP is part of a 10-year program to make U.K. a world-leader in low-carbon propulsion technology.

The catch? These 15 companies have to share a paltry £1.1 million in funding.

And as for Jackson? He’s still raising money for Metalectrique and spreading the word about the potential for aluminum-air batteries to save the planet.

Heaven knows, at this point, it could use it.

Read More

Post a Comment for "Negative? How a Navy veteran refused to accept a ‘no’ to his battery invention"